TikTok eyes a shopping sales goal between $12 billion and $13 billion for the second half this year in the US, according to a 36Kr report on Tuesday. The high target was set after the short video platform fell far below expectations in the first five months. The report quoted key data from Tabcut, a […]]]>

TikTok eyes a shopping sales goal between $12 billion and $13 billion for the second half this year in the US, according to a 36Kr report on Tuesday. The high target was set after the short video platform fell far below expectations in the first five months. The report quoted key data from Tabcut, a […]]]>

TikTok eyes a shopping sales goal between $12 billion and $13 billion for the second half this year in the US, according to a 36Kr report on Tuesday. The high target was set after the short video platform fell far below expectations in the first five months.

The report quoted key data from Tabcut, a Chinese firm that tracks TikTok Shop’s performance, indicating that TikTok generated less than $2 billion in the US shopping business from January to May 2024.

Why it matters: The potential ban TikTok faces in America seems to have already hurt its growing e-commerce business in its largest user base country.

Details: TikTok, the international version of Douyin, was reportedly hoping to expand its US e-commerce business tenfold to as much as $17.5 billion this year, according to a January report from Bloomberg. TikTok has so far only accomplished 11.4% of its GMV goal in the past 5 months, the 36Kr report said.

- TikTok hosted a small closed-door meeting in Shenzhen in mid-May, 36Kr added, where it invited its key domestic sellers to convey a message that the platform “remains optimistic about its prospects in the US market despite facing a political headwind.” The company also assured attendees that TikTok has comprehensive contingency plans in place even in the “worst-case scenario.”

- As the latest effort to counter the US government’s request to divest or ban the app, TikTok parent ByteDance has appointed John Rogovin, a former lawyer of Warner Bros, as its global general counsel. The company sued the US government in May with the aim of blocking a law requiring it to sell its US operation or face a total ban. In the appointment announcement, TikTok said Rogovin will report to ByteDance CEO Liang Rubo, and indirectly to TikTok chief Shou Chew.

Context: TikTok Shop officially entered the US market in September 2023, although little official data has been given to the outside world regarding its merchants and sales. The platform has grown to 170 million users in the American market, according to figures released in January, up from 150 million last year.

]]> TikTok owner ByteDance has surprised the artificial intelligence industry with the ultra-low cost of its Doubao model, which the company said is capable of processing 2 million Chinese characters, equivalent to 1.25 million tokens, for RMB 1 ($0.14). OpenAI’s most advanced multimodal model, GPT-4o, also unveiled this week, comes in at $5 per million input […]]]>

TikTok owner ByteDance has surprised the artificial intelligence industry with the ultra-low cost of its Doubao model, which the company said is capable of processing 2 million Chinese characters, equivalent to 1.25 million tokens, for RMB 1 ($0.14). OpenAI’s most advanced multimodal model, GPT-4o, also unveiled this week, comes in at $5 per million input […]]]>

TikTok owner ByteDance has surprised the artificial intelligence industry with the ultra-low cost of its Doubao model, which the company said is capable of processing 2 million Chinese characters, equivalent to 1.25 million tokens, for RMB 1 ($0.14). OpenAI’s most advanced multimodal model, GPT-4o, also unveiled this week, comes in at $5 per million input tokens handled.

“A good model works well and is affordable to everyone,” Tan Dai, president of Volcano Engine, ByteDance’s cloud computing services unit, said at an event on Wednesday. “Large usage polishes a good model and dramatically reduces the unit cost of model inference,” he added.

Why it matters: The radical pricing, which Tan explained is achieved through model structuring and hybrid scheduling of cloud computing power, is likely to initiate a price war in China’s AI field after a battle on parameters.

Details: ByteDance’s Doubao large model family consists of nine versions, ranging from a “lite version” to the advanced Doubao Pro, which is able to deal with up to 128,000 token inputs. The range also includes models centered on generating pictures and virtual characters.

- The company did not disclose how many parameters it used to train its most powerful Doubao Pro model.

- The Doubao LLM family shares the same name as ByteDance’s ChatGPT alternative, a free AI bot that the company says has 26 million monthly active users.

- The Doubao model is now open to external developers and other interested parties for cooperation via Volcano Engine, though this comes months after tech rivals Alibaba and Tencent gave enterprise customers access to their models last April and September, respectively.

Context: Earlier this year, ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming criticized employees for not being “sensitive enough” to the emergence of new technologies like ChatGPT in an internal meeting, saying that discussions among staff over ChatGPT only started in 2023. His remarks came after the company had already launched the Doubao chatbot in the second half of last year.

]]> TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew told the platform’s users that “we aren’t going anywhere” after US President Joe Biden signed the sell-or-ban bill targeting the app into law, giving TikTok’s Chinese parent company nine to 12 months to divest. “The facts and the Constitution are on our side and we expect to prevail again,” Chew […]]]>

TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew told the platform’s users that “we aren’t going anywhere” after US President Joe Biden signed the sell-or-ban bill targeting the app into law, giving TikTok’s Chinese parent company nine to 12 months to divest. “The facts and the Constitution are on our side and we expect to prevail again,” Chew […]]]>

TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew told the platform’s users that “we aren’t going anywhere” after US President Joe Biden signed the sell-or-ban bill targeting the app into law, giving TikTok’s Chinese parent company nine to 12 months to divest.

“The facts and the Constitution are on our side and we expect to prevail again,” Chew said in a video on Wednesday.

Why it matters: The passing of the bill after months of threats is a clear wake-up call for other Chinese apps that see the US as a top destination for their business expansion or have already entered the market there.

Details: The countdown to the forced sale of TikTok began when Biden signed the bill on April 24, but the short video app’s 170 million American users will continue to have access to it during this period. TikTok is expected to robustly challenge the move in the US courts.

- The law comes as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken begins his visit to China, where he expects to meet the country’s foreign minister Wang Yi.

- Former editor-in-chief of Chinese media outlet Global Times, Hu Xijin, who is known for his nationalist stance, wrote on X that TikTok should “fight to the end”, hours after the Senate ruled on the platform on Wednesday. He said he believes it will be “meaningless” if ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming “loses this career and only gets some money.”

- On Wednesday, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs commented it had nothing more to add to the country’s stance on the TikTok ban as the government institution said it has already made clear its position that there would be “no fairness to speak of” if the US uses national security reasons to ban foreign companies.

Context: TikTok, along with its Chinese owner ByteDance, spent over $7 million on in-house lobbyists and digital ad campaigns this year in an effort to avert the bill passing, according to lobbying disclosure reports cited by CNBC.

]]> TikTok’s efforts to continue operating in the US under Chinese parent company ByteDance appear doomed after a majority of House lawmakers passed a bill that aims to force the Beijing headquartered tech firm to divest from the wildly popular short video platform or see it removed from app stores in the country. The bill still […]]]>

TikTok’s efforts to continue operating in the US under Chinese parent company ByteDance appear doomed after a majority of House lawmakers passed a bill that aims to force the Beijing headquartered tech firm to divest from the wildly popular short video platform or see it removed from app stores in the country. The bill still […]]]>

TikTok’s efforts to continue operating in the US under Chinese parent company ByteDance appear doomed after a majority of House lawmakers passed a bill that aims to force the Beijing headquartered tech firm to divest from the wildly popular short video platform or see it removed from app stores in the country. The bill still needs to pass the Senate, but President Joe Biden has indicated he will sign it into law if it reaches his desk.

The Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted 352-65 on the bill. Of the 65 legislators who voted against it, 50 were Democrats, casting some uncertainty on whether the bill will pass in the Democrat-majority Senate. The potential legislation is also likely to face legal challenges from TikTok.

Why it matters: If ByteDance agrees to sell TikTok, one of China’s most successful apps worldwide, it would bring the Beijing-based company billions of dollars in immediate income, but the longer-term impact on the firm’s value is uncertain. The tug-of-war over the app also reflects the high-profile tensions between the US and China.

Details: TikTok labeled the House’s voting process “secret” in a statement released after the result. The platform insisted on characterizing the bill as a “ban”, while emphasizing that it hosts 170 million users and 7 million small businesses in the US market in a post on X, formerly Twitter.

- Chinese nationalist Hu Xijin, who previously served as editor-in-chief of the state-run Global Times newspaper, said in a recent social media post that the US’s concern over TikTok’s threat to national security is “grossly exaggerated,” and that this is a fact “everyone in the world knows.” The commentator implored the short video app not to “get weak in the knees,” adding that it will share a bright future if it wins this “war.”

- The video-sharing platform sent local users in the US a pop-up notification last week encouraging them to call their political representatives and urge them to fight against the bill. The average TikTok user in the US is an adult “well past college age,” chief executive Shou Zi Chew revealed in his testimony on Capitol Hill last March.

- While Biden has shown broad support for the bill – despite his election campaign recently joining the platform – his rival in the upcoming US presidential election, Donald Trump, has made a U-turn on the legislation, voicing concerns that banning TikTok would only empower Facebook owner Meta. “There are a lot of young kids on TikTok who will go crazy without it,” Trump said in a recent CNBC interview, despite his administration also previously attempting to force ByteDance to sell the app.

Context: According to OpenSecrets, a nonprofit organization that tracks lobbying data, ByteDance spent a record $8.74 million on federal lobbying last year, nearly double its spending in 2022.

]]> On Jan. 13, Tencent announced that its hit game Honor of Kings would resume livestreaming on Douyin (China’s TikTok sibling) five years after it was banned following a copyright infringement case. In 2016, Tencent sued ByteDance for livestreaming the online game on its subsidiary video platform Xigua. In 2019, a court ruling in Guangzhou stated […]]]>

On Jan. 13, Tencent announced that its hit game Honor of Kings would resume livestreaming on Douyin (China’s TikTok sibling) five years after it was banned following a copyright infringement case. In 2016, Tencent sued ByteDance for livestreaming the online game on its subsidiary video platform Xigua. In 2019, a court ruling in Guangzhou stated […]]]>

On Jan. 13, Tencent announced that its hit game Honor of Kings would resume livestreaming on Douyin (China’s TikTok sibling) five years after it was banned following a copyright infringement case. In 2016, Tencent sued ByteDance for livestreaming the online game on its subsidiary video platform Xigua. In 2019, a court ruling in Guangzhou stated that ByteDance platforms were prohibited from livestreaming Honor of Kings without Tencent’s permission.

Why it matters: The return of Honor of Kings to Douyin signifies a further thawing of the relationship between Tencent and ByteDance. Tencent has been gradually lifting restrictions on ByteDance, as its competitor has begun scaling back its gaming interests in recent months.

Details: Tencent’s Honor of Kings is expected to start livestreaming on Douyin on Jan. 21, with game streamers invited to participate in the splashy return, as announced on the game’s page on China’s Twitter-like platform Weibo.

- Tencent Games plans to conduct testing of Honor of Kings on Douyin from Jan. 14 to Jan. 17, aimed at avoiding technical issues that may arise during the first live broadcast. From Jan. 18 to Jan. 20, Honor of Kings will host various game-themed activities on Douyin, with invited gaming influencers heading livestream sessions and handing out in-game benefits.

- A gaming industry insider said Tencent’s efforts to reconcile with Douyin stem from a noticeable slowdown in Tencent’s gaming revenue growth since 2022, according to Sina. New player growth and revenue for Honor of Kings have been weaker than in previous years, leading to immense pressure on Tencent’s gaming team, the insider said.

- Another of Tencent’s hit games, PUBG Mobile, has also seen a decline in users, but there are currently no other new hit games to make up for the loss, the same insider added. In December 2023, Tencent released DreamStar, a new party game with the potential to challenge its domestic rival NetEase’s Eggy Party. At this stage it remains uncertain if it will emerge as the firm’s next hit game.

- Both parties may seek further collaboration in the future, as ByteDance has the potential to work with Tencent in areas including joint operations and distribution partnerships, according to the same Sina report. Douyin currently plays a crucial role in the gaming industry in China as a major channel for advertising and new player acquisition, and Tencent cannot afford to ignore it, the Sina report said.

Context: On Jan. 9, TikTok owner ByteDance said it was engaged in discussions with various potential buyers, including Tencent Games, for its gaming assets, according to Reuters. The two giants are discussing a deal involving major games published by ByteDance’s gaming unit Nuverse, as the TikTok owner looks to step back from the gaming industry.

- In November 2023, ByteDance unveiled plans to scale down its Nuverse gaming unit and sell related gaming assets in a strategic shift away from the gaming industry.

- Honor of Kings, a hit multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) game, generated nearly $1.48 billion in 2023 for Tencent, but saw a notable decline compared to the $1.8 billion achieved in 2022, according to market intelligence AppMagic.

TikTok is seeking to significantly expand its e-commerce business in the US, with plans to achieve a tenfold increase in merchandise sales in the world’s largest economy this year, a target of $17.5 billion, Bloomberg reported on Thursday, citing unnamed sources. Why it matters: TikTok’s ambitious goal will see it push harder to redirect users’ […]]]>

TikTok is seeking to significantly expand its e-commerce business in the US, with plans to achieve a tenfold increase in merchandise sales in the world’s largest economy this year, a target of $17.5 billion, Bloomberg reported on Thursday, citing unnamed sources. Why it matters: TikTok’s ambitious goal will see it push harder to redirect users’ […]]]>

TikTok is seeking to significantly expand its e-commerce business in the US, with plans to achieve a tenfold increase in merchandise sales in the world’s largest economy this year, a target of $17.5 billion, Bloomberg reported on Thursday, citing unnamed sources.

Why it matters: TikTok’s ambitious goal will see it push harder to redirect users’ attention from short videos to in-app shopping in a potential threat to established US e-commerce giant Amazon. The move also signals that the ByteDance-owned short video app, which has 150 million users in the US, will compete more directly with its Chinese counterparts Temu and Shein in 2024.

Details: The global value of goods sold on TikTok was expected to reach around $20 billion last year, according to Bloomberg, with its Southeast Asian platforms contributing the bulk of these sales. Singapore-based research company Momentum Works projected in mid-2023 that TikTok Shop was poised to capture a 13.2% share of the Southeast Asian e-commerce market by the year’s end.

- The highest selling products on TikTok Shop are mainly those that more easily lend themselves to promotion by video, such as clothing and beauty items, while its competitors offer a broader range, from kitchen utensils to digital products.

- Shortly after TikTok Shop went live in the US in September, the hit social media platform experienced early success at its first Black Friday and Cyber Monday events, with the major shopping days seeing more than 5 million new customers from the US make purchases on TikTok.

- Meanwhile, TikTok announced this week that transaction fees for merchants in most product categories will increase to 6% of each sale starting in April, and by July, these will rise again to 8%. TikTok Shop currently charges a commission of 2% plus 30 cents per transaction. The change is likely to have an impact on profit margins for store operators.

Context: Since its initial trial in 2021, TikTok’s foray into e-commerce has sought to replicate the proven path taken by its Chinese counterpart Douyin in the online retail field, guiding loyal users previously attracted by viral short videos to engage in shopping on the platform.

- Indonesia, the first country in which TikTok Shop launched, banned online shopping on social platforms in September, pointing to the protection of small businesses and user data, and forcing TikTok Shop to suspend operations. Despite this setback, TikTok quickly made a comeback in Southeast Asia’s most populous nation through a deal with local company GoTo backed by a $1.5 billion investment.

A federal judge has blocked a law in the US state of Montana that sought to bar the use of TikTok, saying it “oversteps state power”, a month before the ban was due to take effect. Why it matters: The move suggests efforts to prohibit use of the Chinese-owned video sharing app in the US […]]]>

A federal judge has blocked a law in the US state of Montana that sought to bar the use of TikTok, saying it “oversteps state power”, a month before the ban was due to take effect. Why it matters: The move suggests efforts to prohibit use of the Chinese-owned video sharing app in the US […]]]>

A federal judge has blocked a law in the US state of Montana that sought to bar the use of TikTok, saying it “oversteps state power”, a month before the ban was due to take effect.

Why it matters: The move suggests efforts to prohibit use of the Chinese-owned video sharing app in the US will face significant legal challenges. Montana was the first state set to implement a blanket TikTok ban.

Details: In a statement, the US District Judge Donald Molloy said the ban targets “China’s ostensible role in TikTok” rather than protects Montana consumers.

- “We are pleased the judge rejected this unconstitutional law and hundreds of thousands of Montanans can continue to express themselves, earn a living, and find community on TikTok,” an account called TikTok Policy posted on social media platform X.

- However, the office of Montana’s attorney general signaled it was not giving up on a ban, saying “the analysis could change as the case proceeds,” and noting that it looked forward to “presenting the complete legal argument to defend the law.”

- The ByteDance-owned video platform filed a federal lawsuit against Montana in May, claiming the law “unlawfully abridges one of the core freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment,” days after the state passed a law to ban the widely popular app across the state. Senate Bill 419, the initial ruling to ban TikTok in Montana from Jan. 1 2024, outlined a concern that the app accessed data against users’ will and shared it with the People’s Republic of China. An additional consideration for the ban was that it promoted dangerous social media challenges that threatened the health and safety of Montanans.

- TikTok’s Chinese links have been a focal point of running controversy in the US, where the app says it has 150 million users. Inadequate protection of minors’ data is another legal fight the platform has been dealing with.

Context: TikTok has continued to face criticism during its rise in the US, but its popularity and ad revenue point to a continued upward trend in use of the app nationwide. Its parent company ByteDance reportedly generated $54 billion globally in the first half of 2023, a figure close to Facebook owner Meta’s $60.6 billion. The video platform also officially launched an in-app e-commerce feature in September.

]]> Chinese video giant ByteDance will conduct a new round of layoffs from its virtual reality arm Pico as demand for headsets was not “as fast as expected,” said chief executive Henry Zhou, acknowledging at an internal meeting that projections for VR had been overly optimistic. Why it matters: This large-scale downsizing is the latest restructuring […]]]>

Chinese video giant ByteDance will conduct a new round of layoffs from its virtual reality arm Pico as demand for headsets was not “as fast as expected,” said chief executive Henry Zhou, acknowledging at an internal meeting that projections for VR had been overly optimistic. Why it matters: This large-scale downsizing is the latest restructuring […]]]>

Chinese video giant ByteDance will conduct a new round of layoffs from its virtual reality arm Pico as demand for headsets was not “as fast as expected,” said chief executive Henry Zhou, acknowledging at an internal meeting that projections for VR had been overly optimistic.

Why it matters: This large-scale downsizing is the latest restructuring effort by ByteDance in response to dim prospects in the VR industry. Despite significant investments in technology and marketing over the past two years, which failed to yield satisfactory sales results, the company has stated its intention to keep its hardware team intact.

Details: The biggest overhaul since Pico was acquired by the TikTok owner two years ago was announced in a ten-minute meeting on Tuesday, with staff from sales, videos, and platform operations hit the most.

- Although the exact percentage of layoffs was not disclosed by the company, a source close to Pico told local media outlet VR Tuoluo saying around half of its VR staff would be affected.

- In February, Pico slashed nearly a third of its positions, equivalent to hundreds of jobs, mere months after ByteDance launched the flagship Pico 4 VR headset, benchmarked against Meta’s Quest 2. Recent layoffs will shrink the workforce to only a few hundred employees, down from a peak headcount of over 2,000.

- Affected employees will be compensated based on their years of service plus one month’s salary, according to Tencent News.

Context: ByteDance acquired Pico for approximately RMB 5 billion in 2021, and launched an extensive marketing campaign for the Pico 4 standalone VR headset when it was launched a year later. The company enlisted musician Leah Dou and ping-pong star Sun Yingsha as spokespeople, covering major shopping malls and bus stops with advertisements.

- The TikTok owner has high hopes for its VR business, as Pico founder and president Henry Zhou said at last year’s launch event, expecting the headset to sell more than 1 million units eventually. However, early this year, the company lowered its sales target to “slightly over 500,000 units” due to disappointing initial results.

- The Pico 4 boasts a total of 561 apps, according to figures compiled by VR Tuoluo, surpassing Quest’s 532. The report quoted a source as saying ByteDance had spent at least several billion yuan on building a content ecosystem within Pico.

Crystal of Atlan (CoA), the new action role-playing game developed by ByteDance’s video game company Nuverse, was the eighth best-selling mobile game on iOS in China in July, according to local media outlet GameLook, despite only launching on July 14. Why it matters: The new game has the potential to be a breakout hit for […]]]>

Crystal of Atlan (CoA), the new action role-playing game developed by ByteDance’s video game company Nuverse, was the eighth best-selling mobile game on iOS in China in July, according to local media outlet GameLook, despite only launching on July 14. Why it matters: The new game has the potential to be a breakout hit for […]]]>

Crystal of Atlan (CoA), the new action role-playing game developed by ByteDance’s video game company Nuverse, was the eighth best-selling mobile game on iOS in China in July, according to local media outlet GameLook, despite only launching on July 14.

Why it matters: The new game has the potential to be a breakout hit for ByteDance, which has been aiming to develop its own successful mobile title in the wake of HoYoverse’s global success with Genshin Impact. In the second half of July, Crystal of Atlan’s revenue only ranked behind Tencent’s Honor of Kings, NetEase’s Justice Online, and Tencent’s PUBG Mobile, GameLook reported. Fueled by the success of the new game, Nuverse’s July revenue saw a remarkable 109% month-on-month increase.

Details: Based on data from Sensor Tower, CoA’s iOS revenue surpassed RMB 210 million ($29 million) in July. GameLook predicted that the revenue across all platforms amounted to RMB 600 million ($83 million) for the same month.

- Crystal of Atlan is an action role-playing DNF (Dungeon ’n’ Fighter) game that uses 3D graphics and open-world scenarios. Its anime style resembles Genshin Impact and Honkai: Star Rail, both of which were launched by HoYoverse.

- In May, according to CoA’s official Weibo account, the number of pre-registered players reached 8 million.

- ByteDance is actively promoting the game on its short-video platform Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), using internal advertising resources to enhance the game’s visibility. A large number of gaming KOLs introduced the gameplay via videos and broadcasts on Douyin to attract domestic players.

- As of August 8, the hashtags #CoA and #CrystalofAtlant have collectively reached more than 3.5 billion views on Douyin, according to a report by 36Kr. Additionally, ByteDance also recruited KOLs on Chinese broadcast platforms Huya and Betta, to increase publicity for the game. Given the outlay on marketing, some analysts have suggested that maintaining the title’s high profile may prove a challenge in the months ahead.

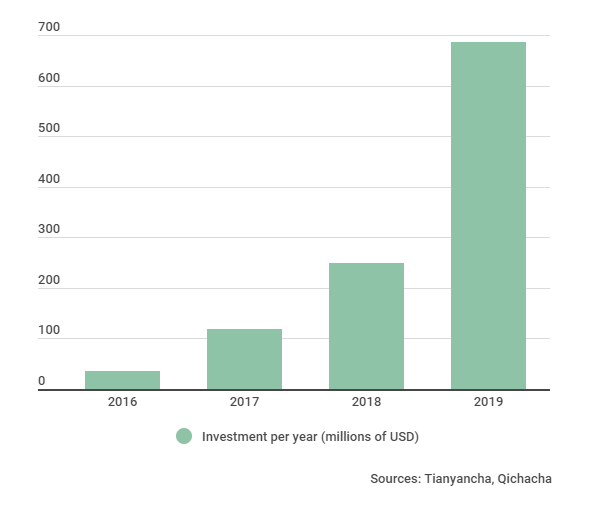

Context: ByteDance established Nuverse in 2019, announcing its entry into the gaming sector. In 2021, ByteDance acquired game studio Moonton and C4games for RMB 10 billion and equity worth RMB 15 billion, according to 36Kr.

- On July 13, Moonton launched the fantasy role-playing card game Watcher of Realms in the global market. The revenue of this game reached approximately RMB 70 million ($9.6 million) in the first month, according to GameLook.

- In 2023, NetEase’s Justice Online and HoYoverse’s Honkai: Star Rail are the two most prominent new titles in China’s mobile game market.

- In July, Justice Online, the martial arts role-playing game launched by NetEase on June 30, ranked seventh with a revenue of $63.3 million.

- In May, Hoyoverse’s new hit game Honkai: Star Rail earned approximately RMB 1.2 billion ($168 million) in the first month since its global launch on April 26.

Douyin, TikTok’s Chinese counterpart, has established a new department dedicated to entertainment ventures, according to a Monday report by 36Kr citing multiple sources. The move aims to centralize the management of activities ranging from live-streaming programs and variety shows to dramas and music. Why it matters: Douyin’s emphasis on cultural and entertainment content not only […]]]>

Douyin, TikTok’s Chinese counterpart, has established a new department dedicated to entertainment ventures, according to a Monday report by 36Kr citing multiple sources. The move aims to centralize the management of activities ranging from live-streaming programs and variety shows to dramas and music. Why it matters: Douyin’s emphasis on cultural and entertainment content not only […]]]>

Douyin, TikTok’s Chinese counterpart, has established a new department dedicated to entertainment ventures, according to a Monday report by 36Kr citing multiple sources. The move aims to centralize the management of activities ranging from live-streaming programs and variety shows to dramas and music.

Why it matters: Douyin’s emphasis on cultural and entertainment content not only enriches its product ecosystem but, more importantly, helps the platform to further diversify its revenue streams.

Details: Chen Duye, head of the recently established division and previously in charge of Ocean Engine, ByteDance’s marketing platform for business promotions across its various apps, will directly report to Han Shangyou, who now holds a prominent position within Douyin.

- Live broadcasts, particularly sports events and concerts, will take priority within the newly-established department, according to 36Kr, due to Douyin getting a taste for broadcasting major events over the past year.

- Official data reveals that 10.6 billion cumulative viewers tuned in to watch the 2022 Qatar World Cup on Douyin. The leading short video platform reportedly spent over RMB 1 billion to secure broadcasting rights.

- Amid COVID-19 restrictions impacting offline entertainment, Chinese-operated short video platforms recognized online events as a source of growth. Douyin, along with competitors Kuaishou and WeChat Channel, organized various concerts and live events featuring renowned musical artists, which has proven effective in drawing user engagement.

- Variety shows, traditionally confined to television or long-form video platforms, have often been constrained by funding limitations during their pre-project phases in China. Nonetheless, the report highlights Douyin’s current efforts to create more original reality TV and variety shows, subsequently monetizing on an uptick in popularity. This involves various approaches, including live commerce activities on the platform and the introduction of content-charging within the platform.

- Short-form dramas have also become a growing focal point for Douyin and its rival Kuaishou, as they strategically monetize their extensive user base. According to data revealed by Kuaishou, by the end of 2022, short dramas on the app attracted up to 260 million active viewers a day, with paid users for short dramas increasing by over 480% in the first quarter compared to a year earlier. While both companies did not provide specific figures, Douyin reported a 72% year-on-year revenue growth in the same sector in 2022.

Context: As of last December, the China Internet Network Information Center reported that over 70% of the Chinese population had accessed short videos, highlighting the significant reach of these platforms as mainstream entertainment channels across the country. The report also noted that individuals spent an average of 2.5 plus hours on the platforms every day.

]]>

TikTok is set to expand its online retail business to the US in early August, according to the Wall Street Journal, in a bid to replicate rivals Shein and Temu’s success in the world’s second-largest e-commerce market. The short video app was thought to be ready to launch the service earlier this year, but delayed […]]]>

TikTok is set to expand its online retail business to the US in early August, according to the Wall Street Journal, in a bid to replicate rivals Shein and Temu’s success in the world’s second-largest e-commerce market. The short video app was thought to be ready to launch the service earlier this year, but delayed […]]]>

TikTok is set to expand its online retail business to the US in early August, according to the Wall Street Journal, in a bid to replicate rivals Shein and Temu’s success in the world’s second-largest e-commerce market. The short video app was thought to be ready to launch the service earlier this year, but delayed the move in May amid concerns from merchants over geopolitical tensions, as previously reported by the WSJ.

Why it matters: The move indicates that TikTok is aiming to earn more revenue from its largest audience market, despite continued threats by American politicians over what they see as the firm’s links to the Chinese authorities. The short video operator has reportedly set a goal for its global e-commerce operation to increase its total sales more than fourfold this year to $20 billion.

Details: On a page called TikTok Shop Shopping Center, users can browse and purchase products, though the model differs slightly from its initial plan to establish a third-party sellers’ platform.

- TikTok will store and ship products for Chinese manufacturers and merchants, from clothing and electronics to kitchen utensils, while also being responsible for marketing, transactions, logistics, and after-sales services, according to the WSJ report.

- Under the so-called “full-service model,” which is currently used by Chinese cross-border e-commerce platforms such as Temu, the popular short-form video streaming platform would only pay Chinese suppliers once US-based clients have placed orders to avoid “inventory buildup.”

- TikTok’s first expansion of its e-commerce outside of Asia came in the UK in 2021, but selling products through live streaming or short videos – a popular approach in China – has not fully appealed to consumers in that country.

Context: The short video app, owned by Beijing-based ByteDance, is used by over 150 million users in the US. However, as TikTok steps up its presence in the country’s e-commerce market, it is facing increasingly strict regulatory scrutiny. The Biden administration in March demanded TikTok be sold or potentially face a national ban in its largest market.

- Last September, Temu launched in the US and quickly found success. But it has been in an intense public dispute with Shein, the low-profile fast-fashion giant established in China, in recent months. Temu sued Shein this month in a federal court, accusing it of violating antitrust laws. This came after Shein sued Temu last December, alleging that it had hired social media influencers to defame Shein.

- TikTok’s entry may escalate this competition further, as some of the professional buyers, warehouses, and order managers recruited by TikTok have been poached from these two competitors, according to the WSJ.

Douyin is reportedly abandoning its goal of achieving RMB 100 billion ($14 billion) in total sales this year, as the business’ progress in the first half of 2023 has only reached one-tenth of the yearly target, falling extremely short of internal expectations. Local media outlet LatePost first reported the news on June 10, citing a […]]]>

Douyin is reportedly abandoning its goal of achieving RMB 100 billion ($14 billion) in total sales this year, as the business’ progress in the first half of 2023 has only reached one-tenth of the yearly target, falling extremely short of internal expectations. Local media outlet LatePost first reported the news on June 10, citing a […]]]>

Douyin is reportedly abandoning its goal of achieving RMB 100 billion ($14 billion) in total sales this year, as the business’ progress in the first half of 2023 has only reached one-tenth of the yearly target, falling extremely short of internal expectations.

Local media outlet LatePost first reported the news on June 10, citing a source close to the matter. While GMV is no longer the most important metric for the unit, the report said that exploring various ways to successfully run the food delivery business is now a more urgent priority for TikTok’s Chinese sibling.

Why it matters: Due to a lack of its own delivery logistic team, Douyin has relied on selling higher-priced set meal kits (which cut down the frequency of deliveries) and third-party delivery companies to offer its food delivery service. The approach is currently presenting challenges in scaling up the business.

Details: Starting in mid-2022, the short video platform has been testing food deliveries in Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu. Users in these three cities are able to order food for delivery within Douyin. But unlike market leaders Meituan and Alibaba’s Ele.me, restaurants selling goods on the Douyin platform need to use delivery riders from another service or deliver the food themselves, making the delivery cost run higher.

- Typically priced over RMB 100, meal kit takeaways are designed for several people to share and have longer delivery times compared to other platforms that prioritize individual sales and more timely delivery.

- In contrast to Meituan, which recorded a peak of 60 million in daily order volume for food deliveries last August, Douyin’s takeaway orders have experienced limited growth, with its average daily order volume from January to March reportedly remaining at around 10,000 to 20,000 units.

Context: Meituan and Ele.me now dominate the food delivery market in China, holding a more than 90% share of the market between them, highlighting the challenge for Douyin. Meituan has already begun a counteroffensive to maintain its leading position in the face of this new challenger.

- In March, Meituan introduced a marketing event called Shen Qiang Shou for merchants, which is currently being trialed in Shenzhen and Beijing. The promotional event allows users to purchase discounted coupons through Meituan’s own livestreaming or short-form videos, which can be redeemed for real goods within a specified timeframe.

- For consumers, Meituan conducts regular live commerce promotional events on the 18th of every month, with influential merchants selling discounted goods with the aim of stimulating demand. According to a Meituan statement, takeout vouchers worth RMB 86 million were sold on its first livestream shopping event, which lasted 11 hours on April 18.

The data suggests more than 30% of the Australian population is using TikTok.]]>

The data suggests more than 30% of the Australian population is using TikTok.]]>

TikTok has announced that it has 8.5 million monthly active users in Australia, in the short video platform’s first disclosure of its user numbers in the country. The platform, owned by Beijing-based tech firm ByteDance, also said TikTok is being utilized by 350,000 businesses as a marketing tool to reach and engage new clients in Australia.

Why it matters: The figure suggests that more than 30% of the Australian population is using TikTok. Australia banned TikTok on government-issued devices in April.

Details: Australia joined more than 10 countries (including the US, the UK, Canada, New Zealand, France, Denmark, and India) in banning the use of the ByteDance-owned short video platform on government devices in April.

- Australia’s Attorney-General’s Department said in April that TikTok poses “significant security and privacy risks to non-corporate Commonwealth entities” due to its extensive collection of user data.

- Lee Hunter, TikTok’s Australia and New Zealand general manager, said the company was “extremely disappointed” by the government-level ban, attributing the decision to “politics” instead of facts.

- TikTok set up an Australian branch office in mid-2020 when the video-sharing platform experienced massive user growth in overseas markets.

- TikTok announced it had 150 million monthly active users in the US three days before a congressional hearing in the country attended by TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew on March 23, in an attempt to emphasize the platform’s wide reach across the US and counter a potential nationwide ban.

Context: TikTok has long been questioned by Western countries on whether it shares users’ data with the Chinese government.

- Over half of US states have announced bans on using TikTok on official devices. Montana authorities have announced their intention to begin blocking all residents from accessing the platform from January 2024. TikTok filed a lawsuit against the Montana government shortly after the bill passed in May.

- TikTok is also under scrutiny in Vietnam. The country’s Ministry of Information and Communications stated on Monday that it is holding probes into allegations of illegal and irregular activities by TikTok, and is expected to make a public announcement in July upon completion of the official investigation.

- The Vietnamese government frequently requests social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok remove content it considers illegal, and regularly reports on the number of links or videos removed by each platform. In April, the information ministry said that TikTok may face a ban in the country if it fails to comply with instructions to remove content it deems to be in violation of its rules, according to local media outlet VnExpress.

The new investment fund signals a move by Zhang, who stepped down as CEO of ByteDance in 2021, to diversify his wealth.]]>

The new investment fund signals a move by Zhang, who stepped down as CEO of ByteDance in 2021, to diversify his wealth.]]>

ByteDance co-founder Zhang Yiming has set up an investment fund called Cool River Venture in Hong Kong, targeting tech-related investments.

Why it matters: Since stepping down as CEO of ByteDance in 2021, Zhang has kept a low profile, rarely making public appearances. Incorporated on May 22, the fund signals a move by Zhang to diversify his wealth.

- As Zhang launches systematic personal investment, ByteDance’s widely popular global app TikTok is facing massive challenges over privacy issues and security concerns.

- On May 17, Montana became the first state in the US to ban downloads of TikTok, with legislation taking effect on January 1, 2024. TikTok has filed a lawsuit against the state, arguing that the ban violates constitutional and other laws.

Details: Zhang Yiming remains the second richest person in China with a net worth of $45 billion according to Forbes’ 2023 list of the 10 richest Chinese billionaires. Zhang was surpassed only by Zhong Shanshan, the founder of drinks brand Nongfu Spring, whose wealth is valued at $68 billion.

- Galaxy LLC, registered in the Cayman Islands, is the sole shareholder of Cool River Venture, the Hong Kong companies registry shows.

- In May 2021, 38-year-old Zhang announced he would step down from the role of CEO at TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance. “The impact of technology on society is growing,” he said in a company-wide letter, expressing his interest in the emerging fields of virtual reality, life sciences, and scientific computing.

- A person close to Zhang, cited by 36Kr, stated that since ChatGPT took the world by storm last November, Zhang has been “staying up late” reading papers on AI.

- Zhang established a RMB 500 million education fund in his hometown Longyan in southeast China’s Fujian province after his resignation. His aim is to support vocational and arts education. He added another RMB 200 million to the fund this month.

Context: Setting up a personal investment fund or family office, or taking roles in other venture capital firms has been a popular trend among successful Chinese tech founders to manage their wealth.

- Alongside Meituan’s co-founder Wang Xing and Li Auto’s CEO Li Xiang, Zhang Yiming is a limited partner of Beijing-based venture capital firm Source Code Capital. Wang Xing led a $530 million funding round for Li Auto as an angel investor in 2019.

- Joe Tsai, Alibaba’s co-founder, has been managing his wealth and investments through his Hong Kong-based family office, Blue Pool Capital. Tsai’s family office investments range from sports and healthcare to crypto and blockchain.

With its peak daily order volume for food deliveries surpassing 60 million last year, Meituan continues to sit pretty at the top of the tree when it comes to China’s local life services sector. The app spans everything from movie tickets and restaurant bookings to medical appointments, and recorded a total of 677.9 million users […]]]>

With its peak daily order volume for food deliveries surpassing 60 million last year, Meituan continues to sit pretty at the top of the tree when it comes to China’s local life services sector. The app spans everything from movie tickets and restaurant bookings to medical appointments, and recorded a total of 677.9 million users […]]]>

With its peak daily order volume for food deliveries surpassing 60 million last year, Meituan continues to sit pretty at the top of the tree when it comes to China’s local life services sector. The app spans everything from movie tickets and restaurant bookings to medical appointments, and recorded a total of 677.9 million users making transactions in 2022.

Yet Meituan’s dominance is increasingly facing challenges. Major Chinese companies including social media platform Xiaohongshu and ByteDance-owned TikTok sibling Douyin have been making inroads into the local life services market as Covid restrictions have eased. By linking consumers with nearby service providers or merchants and encouraging them to make purchases digitally before going to have the experience offline, these newcomers are looking to such transactions as a way to monetize their huge user bases.

For the moment, Meituan claims to be unperturbed. Meituan CEO Wang Xing described Douyin’s expansion into food delivery as having “a limited impact” on the company during its Q1 earnings call. However, the delivery platform recently made takeout livestreaming a monthly event and has launched group-buy delivery services in what many see as a bid to stay competitive in the face of these new entrants.

The total size of the local life services market is expected to reach RMB 35 trillion in China by 2025, though its online penetration rate was only 12.7% in 2021, according to data from Chinese research firm iResearch and cited by Chinese media outlet 21jingji, meaning there’s still plenty to play for.

Here’s a short introduction to new players in this vibrant market.

Xiaohongshu

Experience-sharing lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu, the latest major entrant to this competitive sector, has over 260 million monthly active users. The platform has maintained a thriving user base and sense of community for years and serves as a lifestyle search engine for many of its users. Now, it is making one of the biggest moves in the local life sector.

Xiaohongshu is currently inviting caterers and service providers to test the sale of group-buying packages on its platform. Participating merchants can sign up without paying a deposit or commission to Xiaohongshu for revenue earned through the service, according to tech media outlet GeekPark. Meanwhile, the platform’s influencers are able to earn commission by posting information about retailers that offer group buy options.

If the Shanghai-based company can leverage its feed algorithms while encouraging users to complete transactions within the app, it may see Xiaohongshu emerge as a serious challenger to Meituan, while also accelerating the company’s monetization quest. In 2020, 80% of Xiaohongshu’s revenue was generated by ads, the Financial Times previously reported, citing research firm LeadLeo, but the company is increasingly looking to diversify its revenue streams.

READ MORE: Xiaohongshu bets on e-commerce livestreaming to accelerate monetization: report

Douyin

Douyin has made significant strides in expanding its presence in the local life market, with its services sector reportedly generating over RMB 77 billion ($11.1 billion) in total sales last year, while advertising revenue amounted to just RMB 8.3 billion.

Growth in the platform’s brightest business continues to be strong. Local media outlet 36Kr reported that the unit generated more than RMB 10 billion in GMV in every single month in the first quarter of this year.

The TikTok sibling app has expanded its offerings to include group-buy delivery, sightseeing tickets, hotel reservations, and manicures in recent months. In mid-2022, Douyin allowed short video viewers to order meals directly on the app through a mini-program operated by Alibaba’s food delivery service Ele.me. In March, the service was introduced to 15 new cities, expanding the service to a total of 18 locations in China.

These efforts reflect the fact that ByteDance, Douyin’s owner, is stepping up its push to monetize users on the widely popular platform.

The head of Douyin’s local life business, Zhu Shiyu, recently stated that life services was a vast market worth more than ten trillion yuan, and that only a small proportion of transactions were currently being conducted online.

Kuaishou

Kuaishou, another leading short video-sharing platform in China with 366 million daily active users, has been expanding its presence in the local life services space in an effort to also capture market share, although it currently has less of a presence than rivals Douyin and Meituan.

Kuaishou had been active in offering lifestyle services in Shanghai, Qingdao, and Harbin, with Hangzhou the next major city to see local services rolled out. Kuaishou aims to provide local life services for different cities through a replicable model developed through experimentation. The short video operator incentivizes local merchants to sign up for the service while supporting local influencers who are willing to promote shops on the app.

Xiaogu, head of Kuaishou’s local life business unit, noted that since it entered the Qingdao market on Feb. 10, it has added over 300 local businesses. Kuaishou reportedly recorded around RMB 5 million in local sales in the seaside city in its first month, and already saw some influencers generate around 200,000 yuan in a single month.

]]> China’s largest gaming firm Tencent can finally advertise on ByteDance apps, in a sign the relationship between the two firms is thawing.]]>

China’s largest gaming firm Tencent can finally advertise on ByteDance apps, in a sign the relationship between the two firms is thawing.]]>

China’s largest gaming firm Tencent can finally advertise on ByteDance apps, according to online gaming analytics platform DataEye, a new milestone in the two companies’ relationship. ByteDance and Tencent have competed fiercely over the years, barring each other from cross-promotion and regularly engaging in legal wrangles. As a result, Tencent games have had limited exposure on ByteDance platforms, while ByteDance’s apps have had little publicity on Tencent platforms.

The latest advertising data shows that Tencent’s war game Return to the Empire and multiplayer role-playing game Naruto have been advertised on Bytedance’s Douyin (China’s TikTok twin), news app Toutiao, and Xigua Video in the past seven days.

Why it matters: The relationship between Tencent and ByteDance has long been tense due to their rivalry in content, video, and gaming. Recent developments show the two companies are moving toward a reconciliation after years of bitter competition.

- On Feb. 7, Douyin and Tencent Video announced an unexpected cooperation, in which the two parties will jointly explore the promotion of videos and the secondary creation of short videos. Tencent has issued a long-term video copyright authorization to ByteDance and clarified secondary video creation rules. On Tuesday, Tencent was able to register the official account of Tencent Video on Douyin. The partnership deal between the two companies has even become a hot topic on microblogging platform Weibo.

- Such reconciliation was unthinkable a few years ago. In the second half of 2021 alone, Tencent sued Douyin 168 times for video rights infringements, with compensation reaching almost RMB 3 billion (or $430 million).

Details: Tencent’s game Return to the Empire has started to place advertisements on ByteDance’s Toutiao and Xigua Video in recent days. The game had previously been advertised mostly within Tencent’s platform, according to DataEye statistics. In addition, ByteDance’s Douyin accounted for about 15% of the gaming ads distribution for another Tencent game Naruto.

- The reconciliation will potentially benefit both sides. Traffic from ByteDance platforms may head in Tencent games’ direction. At the same time, Tencent’s ubiquitous app WeChat could open up to ByteDance and introduce new users to ByteDance apps.

- The promotion of bestselling Tencent games (like Honor of Kings) in Douyin may enrich ByteDance content.

- The move will have repercussions in livestream gaming too. In the future, ByteDance-based games may also enter the WeChat network and WeChat video channel.

Context: Sharing a focus on content and entertainment, Tencent and ByteDance were the top-grossing publishers in global mobile app stores in the first half of 2022. Tencent was the top-grossing publisher in the game and non-game categories, earning about $3.3 billion in the first half of 2022. The figure is almost 153% higher than ByteDance, which came second with $1.3 billion in revenue. Their disputes have been long-lasting:

- In January 2023, Tencent super app WeChat temporarily blocked users from accessing links to ByteDance-owned short video app Douyin.

- In June 2021, ByteDance criticized Tencent’s practice of blocking links to its products on WeChat and QQ in an online post, attaching a 59-page PDF file chronicling incidents of blocking in the past three years.

- In May 2019, Tencent filed two lawsuits against ByteDance, requesting the owner of Douyin stop streaming Tencent’s hit titles CrossFire and Honour of Kings.

- In June 2019, Tencent filed six new lawsuits against ByteDance, demanding the company delete all Honour of Kings gameplay videos from the accounts of six specified users on Toutiao and Douyin. It demanded ByteDance pay RMB 10.8 million (around $1.56 million) in damages.

Chinese tech giant Tencent has launched an AI-powered short video editing tool called Zenvideo.]]>

Chinese tech giant Tencent has launched an AI-powered short video editing tool called Zenvideo.]]>

Chinese tech giant Tencent has launched an AI-powered video editing tool called Zenvideo, integrating a variety of features for short-form video creators, such as text-to-video generation and digital narration.

Why it matters: With its growing emphasis on short video, Tencent is looking to further challenge current market leaders in the sector such as Kuaishou and ByteDance’s TikTok sibling Douyin. Tencent’s new offering comes with similar capabilities to ByteDance’s CapCut, which recently surpassed 200 million monthly active users in the US.

Details: Zenvideo is available to use both through web browsers and WeChat’s mini-program, but is more powerful as a web app. The version within Tencent’s superapp has comparatively limited AI features, only supporting AI painting and digital narration.

- The video editing tool allows users to create short-form videos, with a range of editing options such as filters, visual effects, and digital avatars.

- Unlike ByteDance’s video editing toolCapCut (Jianyin in the Chinese market), Tencent’s new tool can be operated on the web without the need to download an app. Furthermore, users can import Tencent licensed video and audio clips and use them as long as the final work is published on Tencent’s open content platforms. For example, users are able to use music from Tencent’s streaming platforms and take clips from popular Tencent Video TV shows such as The Three-Body Problem and Red Sorghum and edit them for free within Zenvideo.

- According to a notice within the tool, Tencent plans to share revenue with video creators as an incentive to attract more content creators.

Context: This week, Tencent’s super app WeChat also announced several changes to its ecosystem, especially for its short video section WeChat Channels.

- WeChat Channels has an average daily user time of about 40 minutes, which is less than one-third of the two leading short video platforms Douyin and Kuaishou. The latter reached a new high of 134 minutes in the fourth quarter of last year, its latest financial results showed.

- Regarded as “the hope of the whole company” by Tencent CEO Pony Ma, WeChat Channels is planning to launch a paid subscription service and share revenue with creators of short videos. This move is likely to heat up the competition among similar platforms.

ByteDance is keen to develop its own AI language model amid the rise of ChatGPT.]]>

ByteDance is keen to develop its own AI language model amid the rise of ChatGPT.]]>

ByteDance has hired Yang Hongxia, former head of the team overseeing Alibaba’s large AI multi-model M6, to lead its AI Lab and to build its generative large language model (LLM), local tech media outlet 36Kr has reported.

Prior to joining Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba, Yang received her doctorate in statistical science from Duke University and worked as Yahoo’s principal data scientist. Her expertise in cognitive intelligence helped Alibaba launch its 10-trillion-parameter M6, improving the search and recommendation accuracy of shopping app Taobao and payment app Alipay, according to Yang’s account to the ISI World Statistics Conference.

Why it matters: ByteDance is keen to develop its own AI language model, as the success of ChatGPT pushes tech majors to re-evaluate the application of AI in their products and services to stay competitive.

- ByteDance has tapped Yang to lead its language generation model team, a person familiar with the matter told 36Kr, and she is expected to report directly to the company’s vice president Yang Zhenyuan.

Details: ByteDance is reportedly planning to prioritize imaging and language in its AI model, with the former to be integrated into its short video platform Douyin and video-cutting tool CapCut, the company’s two most successful apps alongside Douyin sibling platform TikTok.

- Zhu Wenjia, who currently serves as the head of global search and development for TikTok, has been appointed to oversee the large language and image model teams.

- M6, an abbreviation of MultiModality-to-MultiModality Multitask Mega-transformer, was introduced by Alibaba’s Damo Academy in March 2021. The model contains 10 trillion parameters and is pre-trained to perform multiple tasks, including generating clothing designs based on prompts, offering concise descriptions of e-commerce goods, and answering common questions, the AI model’s website shows.

Context: Major tech companies and AI startups are chasing experienced AI talent as they rush to develop their own AI offerings.

- Yang resigned from Alibaba for personal reasons last September, following the departures of several scientists, such as Jin Rong, ex-Alibaba vice president and associate dean at Damo Academy, and Wang Gang, head of the group’s auto driving lab.

- Another Alibaba VP, Jia Yangqing, also confirmed he had quit the tech giant on Tuesday, with the aim of pursuing a new AI infrastructure venture.

CapCut, an all-in-one video editing app owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has surpassed 200 million monthly active users]]>

CapCut, an all-in-one video editing app owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has surpassed 200 million monthly active users]]>

CapCut, an all-in-one video editing app owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has surpassed 200 million monthly active users, according to a report from Chinese financial media outlet Baijing.

Why it matters: CapCut’s success comes amid an increasingly hostile climate for China-developed apps in the US and European markets, with ByteDance’s TikTok facing restrictions and investigations on multiple fronts.

- The figures make CapCut the second overseas-focused product from ByteDance to achieve more than 100 million MAUs.

Details: CapCut was originally developed by Shenzhen Lianmeng Technology, a startup which ByteDance acquired in 2018 for $300 million. Launched as Jianying in China and designed for both mobile and PC, it offers a range of video editing functions, filters, audio and visual effects, and video templates and is compatible for use with TikTok.

- ByteDance released an overseas version of Jianying in April 2020, rebranding it to CapCut in December 2020.

- According to data from Chinese app analysis platforms Diandian and Data.ai in Baijing’s report, CapCut had more than 200 million MAUs in January. That month also saw CapCut enter the top 30 non-game apps list for iOS and Android devices in China. Its global revenue in January was $800,000, with the US market accounting for more than half of this figure. Although CapCut still has a revenue gap to Meitu’s editing tool BeautyPlus, which tops the list with over $2 million in monthly revenue, it has seen impressive growth, managing to achieve significant monetization in just four months.

- CapCut has largely gained users through in-app promotions on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, and by making its services available for free for two years. Since September 2022, CapCut started charging for premium features, which users can access by monthly or annual subscription packages.

- CapCut Pro’s charges revolve around cloud storage and premium features. The monthly cost of cloud storage is $0.99 for 10GB, $1.99 for 100GB, and $5.99 for 1,000 GB. The premium features are priced at $9.99 for a single month, $7.99 for a continuous monthly subscription, and $74.99 for a full year.

- In October 2022, as part of an update, CapCut launched a PC version, which is compatible with most mainstream social media platforms overseas, making it more attractive to both private customers and enterprise businesses.

- The app also runs a creator recruitment program whereby video creators making popular templates can earn up to $1,000.

Context: TikTok reportedly set a goal of topping 1 billion daily active users worldwide by the end of 2022, testament to the app’s continued growth even as it faces a number of investigations and restrictions around the world.

- On Feb. 27, Canada announced that it was banning the use of TikTok on government-owned devices, following similar moves in the US. The ban came just days after the EU announced similar restrictions for its staff.

- In September, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) warned that the ByteDance-owned video platform could face a $29 million fine for failing to protect child privacy.

- Earlier this year, ByteDance moved Douyin vice president Zhi Ying to TikTok to head up the latter’s products and content businesses, as the Beijing-based company looked to involve more of its successful executives in TikTok’s development.

On Feb. 10, China’s National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA) released its approval list of domestic online games for February 2023 on its official website, with titles by Tencent, ByteDance, and NetEase among those given the green light. Why it matters: The new list is the ninth batch of games approved in China since the […]]]>

On Feb. 10, China’s National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA) released its approval list of domestic online games for February 2023 on its official website, with titles by Tencent, ByteDance, and NetEase among those given the green light. Why it matters: The new list is the ninth batch of games approved in China since the […]]]>

On Feb. 10, China’s National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA) released its approval list of domestic online games for February 2023 on its official website, with titles by Tencent, ByteDance, and NetEase among those given the green light.

Why it matters: The new list is the ninth batch of games approved in China since the NPPA resumed its issuing of licenses in April 2022 following an eight month pause. As with January, the number of new licenses this month exceeded 80, higher than any month in 2022 and a sign that China’s gaming regulators may be returning to a more consistent approach to approvals after months of uncertainty.

Details: Some 87 new domestic games have been granted licenses by the NPPA, including 79 mobile games, seven PC titles, and one game for Nintendo Switch.

- Tencent’s high-profile new game King Chess, a strategy battle mobile game that is part of the company’s attempts to build an Honor of Kings “universe,” was among those gaining approval. The official WeChat account for the game claimed on Feb. 10 that it is still in development and will undergo beta testing in the near future.

- NetEase, another Chinese gaming giant that has struggled for new title approvals in the past 18 months, saw the mobile version of its massively multiplayer online role-playing game Fantasy Westward Journey make the list of February approvals.

- ByteDance has three new titles on the list: The Leader of the Battle from its publisher Ohayoo; Matrix: Out of Control by wholly-owned subsidiary Nuverse; and Hyper Instant Connection by its newly acquired company C4Games (all titles our translations).

Context: China’s gaming industry has been sluggish over the past year due to tightening regulations on the industry and strict limits on young gamers.

- The total revenue of the video games market in China slumped 10.33% to RMB 265.9 billion in 2022, while game users declined slightly, down 0.33% year-on-year to 664 million, according to a report by the country’s semi-official games industry association.

- In August 2021, Chinese authorities restricted the weekly gaming hours for minors under the age of 18 to one hour a day on Fridays, weekends, and public holidays.

- China’s eight-month gaming license freeze was lifted in April 2022, but new approvals remained limited throughout the year. Just 513 game licenses, including 468 domestic games and 45 imported games, were issued over the course of 2022, 38% fewer than in 2021 and only a third of those approved in 2020, according to Caixin’s calculations. Tencent, one of the biggest gaming companies in the world, didn’t receive its first major approval of the year until November.

ByteDance-owned video-sharing platform Douyin, China’s equivalent of TikTok, plans to offer its “group-buying delivery” service in more cities, but has no timeline for a national rollout, TechNode has learned. Why it matters: The gradual entry into the food delivery sector of Douyin, the most popular short-form video app in China with nearly 700 million daily […]]]>

ByteDance-owned video-sharing platform Douyin, China’s equivalent of TikTok, plans to offer its “group-buying delivery” service in more cities, but has no timeline for a national rollout, TechNode has learned. Why it matters: The gradual entry into the food delivery sector of Douyin, the most popular short-form video app in China with nearly 700 million daily […]]]>

ByteDance-owned video-sharing platform Douyin, China’s equivalent of TikTok, plans to offer its “group-buying delivery” service in more cities, but has no timeline for a national rollout, TechNode has learned.

Why it matters: The gradual entry into the food delivery sector of Douyin, the most popular short-form video app in China with nearly 700 million daily active users, poses a serious challenge in an industry which has been dominated for years by Meituan and Alibaba’s Ele.me.

- “We would consider expanding the [“group-buying” packages] feature to more cities in the future depending on the testing results, and there is no detailed timeline yet,” a spokesperson from Douyin’s life services unit told TechNode on Wednesday.

Details: In contrast to the food delivery services offered by its established competitors, Douyin’s “group-buying delivery” service enables merchants to promote and sell food packages that are generally for two or three people, via short videos or livestreams. Packages are then delivered to paying customers within a selected time frame.

- The feature was tested last December in three cities – Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu – before the launch of a self-registration service for local merchants in January.

- Merchants can use the third-party courier platforms that Douyin cooperates with, including SF Express’s SFTC, JD-backed Dada, and Shansong, or choose to deliver themselves.

- The group-buying packages fall under the short video platform’s local life services unit, which encompasses the food and restaurant, in-store business, and hotel and tourism segments. The emerging unit expects total sales to reach RMB 150 billion ($22.2 billion) in 2023, twice its actual GMV of RMB 77 billion in 2022, tech media outlet 36Kr reported earlier this year.

- Only merchants with physical stores can take up the feature in Douyin, which is available at a cost of 2.5%, and 5% to 10% in service fees to the platform and service providers respectively, local media outlet Jiemian reported on Tuesday. If the merchant uses a delivery service in cooperation with the platform, they have to pay about RMB 8 per order.

Context: China’s takeaway market has continued to grow in size in recent years, with Meituan dominating the industry to date. According to a report conducted by Zhiyan Consulting, Meituan took a 69% share of China’s food delivery market in 2020, while Ele.me accounted for 26%.

- Douyin tested a food delivery mini-program called “Xindong Waimai” in 2021, partnering with well-known brands such as HeyTea and KFC, but the platform was never officially launched.

ByteDance has moved Douyin’s vice president Zhi Ying to lead TikTok’s products and content business as TikTok becomes an increased focus of its parent company’s attempts to diversify revenue streams, according to a Wednesday report by local media outlet 36Kr. Why it matters: Zhi Ying’s move reflects the importance of TikTok to ByteDance’s revenue growth, […]]]>

ByteDance has moved Douyin’s vice president Zhi Ying to lead TikTok’s products and content business as TikTok becomes an increased focus of its parent company’s attempts to diversify revenue streams, according to a Wednesday report by local media outlet 36Kr. Why it matters: Zhi Ying’s move reflects the importance of TikTok to ByteDance’s revenue growth, […]]]>

ByteDance has moved Douyin’s vice president Zhi Ying to lead TikTok’s products and content business as TikTok becomes an increased focus of its parent company’s attempts to diversify revenue streams, according to a Wednesday report by local media outlet 36Kr.

Why it matters: Zhi Ying’s move reflects the importance of TikTok to ByteDance’s revenue growth, with the Beijing-based company set to involve more of its successful executives in TikTok’s development. In December, ByteDance also moved Chen Xi, former head of news app Jinri Toutiao, to head up TikTok’s e-commerce product development.

Details: Zhi Ying worked for PricewaterhouseCoopers and Uber before joining ByteDance in 2016, where she led the operation and marketing of short video platform Huoshan. Later, she moved to oversee Douyin’s marketing and ran the company’s video-sharing app Xigua video.

- Zhi is “very competent and has a strong management style, while also being good at expanding business,” sources told 36Kr.

- Several TikTok managers, including those in charge of user growth, content style, and live-streaming, now report to Zhi, while she herself reports directly to Zhu Wenjia, head of TikTok’s products and technology.

- ByteDance’s revenue growth slowed in 2022 and the daily active user growth of its products was lower than expected, CEO Liang Rubo acknowledged at an all-staff meeting held in December. TikTok’s sister app Douyin has not publicly updated its user base numbers since it announced in September 2020 that it had more than 600 million DAU.

- TikTok currently has over 1 billion users worldwide, with the short video app having a global penetration rate of less than 20%, while Douyin has reached nearly 54% in China, LatePost reported in October last year, citing a TikTok staff member.

Context: ByteDance is sending more senior executives from China with successful track records to TikTok at a time when US officials continue to heighten scrutiny of the app. TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew is reportedly due to appear before the US Congress next month in connection with the platform’s privacy and data security.

- More than 25 states in the US have banned TikTok on government-owned devices and a US House panel is set to vote in February on a total ban aimed at blocking TikTok from operating in the US.

- ByteDance is also seeking to expand into overseas markets with its team management platform Lark due to profitability challenges in the domestic market, Chinese media outlet Jiemian reported in early January.

In 2022, TechNode readers gravitate toward several topics: consumer tech, Douyin, Shein, US chip sanctions, and more. ]]>

In 2022, TechNode readers gravitate toward several topics: consumer tech, Douyin, Shein, US chip sanctions, and more. ]]>

Editor’s note: China is on holiday for the Lunar New Year, or Spring Festival, from Jan. 21 to Jan. 27. For the week, TechNode has prepared three yearly summary reports. They include a list of the most-read articles, an in-depth feature on the rising Chinese EV sector, and an analysis of the growth of China’s overseas shopping apps.

In 2022, many Chinese tech companies struggled to keep growing amid slowing demand, drastic Covid control policy changes, and heightened geopolitical tensions.

TechNode looked back on articles published in this tumultuous time and saw readers gravitate toward several topics: new Chinese consumer tech products, the rise of Douyin and Shein in e-commerce, the US’s chip sanctions on the entire Chinese semiconductor sector, and key moves from China’s tech giants.

Below are the 10 articles read the most by TechNode readers in 2022:

1- A guide teaching programmers “to live longer” goes viral on GitHub among Chinese tech workers

A Chinese-language guide on GitHub entitled “HowToLiveLonger” was trending within the Chinese tech community in late April. Despite its serious and scientific tone, the new “guide” appeared to be a pointed joke, taking aim at ongoing overwork practices in China’s tech industry and their impact on employees’ mental and physical well-being. Its popular reception in Chinese tech circles reflected the community’s mood.

2- ByteDance acquires two new entertainment companies

Chinese tech unicorn ByteDance acquired cinema ticketing platform Yingtuobang and online comics service Yizhikan Comics to further ramp up its push into the entertainment market, Chinese media outlet Tech Planet reported in mid-January.

With the new acquisitions, the Beijing-based TikTok developer further expanded the reach of its entertainment empire, which already consisted of short video apps, short- and long-form video platforms, news aggregation services, online novels, gaming, music streaming, idol management, and virtual idols.

3- Tencent reported to be cutting 20% of its workforce

Chinese tech giant Tencent reportedly planned to lay off around 20% of its staff in mid-March, joining a lengthy list of tech firms trimming their workforces since 2021.

Deep-pocketed tech titans such as Tencent and Alibaba, which are generally less vulnerable to small market fluctuations, have largely maintained their headcount until recently. The two giants have not been immune to China’s ongoing economic downturn, regulatory curbs, and international trade tensions.

4- China’s NFT market: Who are the major players, and what makes them different?

In China, the NFT digital art market is bustling with new players and projects. That may come as a surprise for people familiar with China’s strict approach to cryptocurrency, with the country having fully banned crypto trading and mining in 2021. However, China has also embraced controlled versions of blockchain technology, such as the digital yuan, encouraging its growth in various sectors. So far, China has allowed NFTs but banned people from speculating and trading them.

NFTs are viewed more as a derivative of blockchain technology rather than a tradable asset in China. Tech majors such as Alibaba, Tencent, and JD have built their own platforms where users can buy and collect NFTs but are prohibited from trading or reselling their purchases. Most Chinese tech giants don’t even use the term NFT, hoping to stay on regulators’ good side and avoid association with the global crypto market. Instead, they use the term “digital collectible.”

5- The US’s moves to contain China’s semiconductor industry: a timeline from July

In early October, the US announced a new set of semiconductor export restrictions aimed at cutting China off from accessing certain high-end chips and further limiting the country’s ability to make advanced chips themselves.

The US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security issued nine new rules, imposing export controls on advanced chips, transactions for supercomputer centers, and transactions involving certain entities on the Entity List. The rules also imposed new controls on certain semiconductor manufacturing equipment and on transactions for certain integrated circuit end uses.

6- Chinese semiconductor firms bear heavy fallout of US chip sanctions

After the US issued one of the broadest export controls on semiconductor technology to China in a decade in October, China’s semiconductor industry saw its market value tumble. At least 13 China-listed semiconductor firms saw their market value decline more than 10% in less than a week, and five saw a more than 20% decline.